| |

| |

Click on swirl for quick links to individual topics, then respond to any with your thoughts. Give us more info. Ask a question. Drop us a dream…

|

|

Skyhook

A term used by Daniel Dennet in his book Darwin’s Dangerous Idea to illustrate a fantastical, "false" approach to evolutionary development. As if by an illusory hook from the sky or deus ex machina the design of a species could leap forward, rather than being developed infinitesimally by the blind trial and error process of natural selection. Skyhooks don’t work, he says. Prozak takes a "skyhook" approach to her depression by "hooking," seeking to o’er leap the mind numbing pain she feels in an extreme ritual that does land her in a different place. She ends up in a coma, in the hospital, a prolonged dream, where her unconscious does the healing via the Platypus. In the realm of our psyches, if not in science, "skyhooks" while dangerous sometimes work.

< back to top > |

| |

|

|

Ketamine (aka Kit-Kat, Special K)

Drug used as an anesthetic in the experiments with a platypus to insert electrodes under the skin to monitor the brain. It has been used on humans in surgery, and also recreationally in clubs (K-holes). It gives a hallucinatory, out of body experience, where the physical body moves very slowly. Interestingly enough, it is now being investigated as a radical treatment for the rapid relief of chronic depression, in Brisbane of all places. I discovered this after I wrote the play. But there is a quality of lifting out of the body, reaching beyond the self, which Prozak experiences in the “skyhook” which is part of her healing.

|

| |

|

|

Rainbow Serpent

A powerful force in the Australian Aboriginal pantheon of spirits. As with Iris in Greek mythology, a rainbow serves as a bridge between worlds on which the initiate or messenger travels. The dreamer can travel from lower to higher realms on the rainbow serpent’s back. fMRI brain scans produce a pulsating rainbow of colors on a screen, indicating at any given time where the brain’s activity is most intense. Prozak, suspended in the Skyhook, is rising through the rainbows of the Platypus’ brain scan. Journeying to a place where something can shift inside her enough to come back to earth and live out her life. She is traveling into the Platypus’ dream.

See also: "The Mysteries of the Dreaming" by Bruce Corwin

Pictured left: Rainbow Serpent by Joshua Yasseree

|

| |

|

|

Urban Primitive

Ancient beliefs and rituals still have presence in modern, urban societies. There is the desire to mark the body with meaning, ownership, or a significant event, in the widespread appearance of tattoos and body piercing. While considered a fad, or a fashion impulse, it taps into something deeper. Most everyone I ask remembers exactly why, where, and when they got a particular tattoo. For some people it is their only frontier of exploration and expression, the only thing that is truly their own, their body.

See also: RE-search Modern Primitives: An Investigation of Contemporary Adornment & Ritual

< back to top > |

| |

|

|

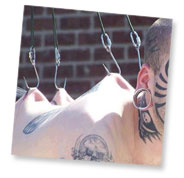

Hooking / Human Suspension

A practice where humans suspend themselves on wires with hooks, inserted directly into their flesh. There are many different positions: O-Kee-Pa, Suicide, Crucifix, Superman, Coma, Falkner, Lotus. Some hooking is done as performance spectacle, but mostly it is done as semi-private rituals of pain and endurance. Groups gather to help each other hook, provide support, and develop safe practices; rigging is an art, and there are good accounts online of what people feel when they hook and why they do it. There are galleries of images and notices of national gatherings called Suscons.

For Prozak "hooking" is a physical way of dealing with the intensity of the mental anguish she feels. She tries to leap into the epicenter of some pain she can tangibly expereince. As if by taking this risk of flight she can conquer her own fear of death, or know what her mother felt so silently when she committed suicide. Some audience view Prozak’s "hooking" as her own suicide attempt, or a death wish, I think it is the impulse that keeps her alive. It is what she is doing in her loud music, piercing, and poetry, trying to find external expression commensurate to the silent desperation, anger, and pain she feels inside. The writing on the "hooking" practice does not talk about masochism, but levels of psychic transformation and healing, and deep listening to the body.

See also: The Alchemy of Body Modification: Pagan Fleshworks and www.bmezine.com

< back to top > |

| |

|

|

Teenage Depression

It’s a time to form an authentic self, to undergo internal revolutions while defying the fire of external criticism, to forge one’s personality as an adult. It’s a noble, challenging time; many cultures have rites of passage to test and bring a young person into society. Yet in our society “teenager” connotes being moody, petulant, apathetic, peer driven, isolated in a world of your own, “depressed” if you will. So “Teenage Depression” is a redundancy, something we’ve come to expect from adolescents, which seems a strange comment on our society. Treating teenagers with anti-depressant medication is problematic, as more studies indicate that Prozac and other medications may increase chances of suicide among teens.

There is something off kilter about anticipating depression for the most exciting time of growth. It’s no wonder that teenagers make their own rituals, clan behavior, if there is no larger role or forum to stretch them, no higher demands made for their entrance into society. Instead in commercial culture there is an intense pressure to conform, not to be queer, not be misshapen, not be ugly, not be a loser. Rather than a positive emphasis on developing a unique self, there is a negative emphasis on banishing parts of yourself to non-being. It’s easy to get caught in the fear of being ridiculed, even by yourself, which compounds feelings of “depression.” The anger of not being who you are then turns inward to strangle that what you might have become. In our society adolescents must be fighters, often in a forum that is hard for adults to understand or shepherd. And it seems as if “depression” is just part of the vocabulary of what being a teenager is now.

The strongest performance of Prozak and the Platypus I have seen was for an audience of teenagers at the New York State Summer School for the Arts (NYSSSA). It was only a reading of the play, but it connected with the teenage audience in a profound way. Students from that evening are still contacting me about doing the play several years later because the play moved them in a way they never forgot. After the show there was an intense discussion, focusing on the character Blue. Mostly a physical and vocal role with very few lines, Blue is the most ephemeral of the characters in the play, and the one that adults either ignore or have the most questions about and want pinned down.

Who is Blue? Eternal voice, a singer, fucked-up angel, depression, the sky, seduction, loss, music, sex, the ocean, a wave, my favorite color, hope, pain, Prozak’s dead mother, a ghost, suicide, a cool chick, the Blues… Her fluidity seems to represent their experience of “depression” in all its varied aspects. She is a state of mind they all have experienced, to some degree cherish and fear, or at least are deeply engaged with and is a part of their daily lives. Blue is present in song and sound, but not in language, so she comes close to their feeling of the inarticulate void, what it is to be “depressed.” From listening I’d say maybe only one, or at most two, of the students had ever known anything close to clinical depression. But the rest had instinctual knowledge of the terrain, fluency with the vocabulary of symptoms and medication, and an acceptance that “depression” is a part of their daily lives.

What moves them about the play is that Prozak, the central character, makes a choice to engage with Blue, to pass through the fire of her own sadness and even death. She is supported by her music, an imaginary animal guide, and a father who does not abandon her. It’s a very hopeful and romantic premise, whose truth is supported by the actual emotional experience of the play. Adults love many different aspects of the play: its whimsy; its science, the music, and treatment of a variety of themes. But those who really take it for a ride seek the assurance that it’s possible to go through some transformation inside, often in explicable to others, but vital to themselves and come out the other side.

The theater work I have done with diverse groups of teenagers has always left me inspired by their creative ability, capacity for truth, willingness to take huge risks, and support each other. Anything phony loses attention fast, but what is powerful, true, and heartfelt, ignites their own ability to communicate, and watch out when they speak. It’s powerful and articulate, demands to be heard.

So the frequency and presence of “teenage depression” strikes me as the flip side of their tremendous potential, which is too new and insistent to be entirely denied. And it strikes me as being particularly important to recognize the avenues they find towards self expression and growth, if our society is not giving guidance or demanding much, (beyond their becoming avid consumers). Music and poetry is a big sphere accessible to many where channels can open and voices can be heard inside and without.

< back to top > |

| |

|

|

Ornythoryncus Anatinus

The duck-billed platypus is a primitive creature. Classified as a monotreme, it is one of three species, the other two being echidnas, long and short beaked spiny anteaters, also natives to Australia, who broke off from the mammalian line over 140 million years ago, and have not changed much since. The platypus lays eggs like a reptile or bird, but is warm-blooded, furry and suckles its babies like a mammal. It is a "one-holer" or "cloacal" since it uses one tract as both anus and birth canal. The platypus was thought to be a clever hoax when it was presented to scientists at the British Museum in London in 1798, who thought someone had stitched the thing together. “Flat foot” - what platypus means in its Latin roots - still swims and waddles streambeds along the Eastern coast of Australia and Tasmania. It holds a fascination for adults and children, witness the many webbed sites (the best is below). It is certainly what provoked my writing this play, when I read an article in the Science Times: "Does a Platypus Dream?" about sleep experiments with Ornythoryncus Anatinus. In one flash, the characters suddenly appeared to me: young girrrl rocker, Prozak, Arvin her father the scientist, Frankie, the platypus, and Blue, an ineffable spirit I’m still writing to try to catch up with them… especially Frankie who inserts himself into e-mails and daily discourse.

See also: www.platypus.org.uk

< back to top > |

| |

|

|

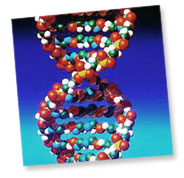

Sleep Cycles

Prozak and the Platypus is based on an experiment with platypuses conducted by Dr. Jerome Seigel, who runs a center for sleep research at the Veteran’s Medical Center in Sepulveda, California, as part of the UCLA Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences department. When I was doing research for the play, Dr. Seigel was kind enough to show me around his laboratory, where the current focus is investigations into sleep apnea, a medical condition in which the windpipe collapses during sleep causing suffocation. He conducted the platypus experiment several years prior in Australia at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, because platypuses are indeed delicate, and do not travel well. He told me about going out in a boat at night to capture a platypus, viewed as a bit of a pest by local farmers, and showed me videos of the experiment, (mostly of a platypus swimming around in a tank and devouring "yabbies" - small crayfish-like creatures it breaks the neck of and eats). Dr. Seigel gave me invaluable details about the experimental process, from controlling cycles of daylight, to keeping electrics away from the platypus tank that ended up in the laboratory scenes in the play. I also gained a sense of how this experiment fit into his investigations of other animals, with interesting sleep patterns, such as dolphins, who "sleep" by swimming in circles, and resting different hemispheres of their brain.

Sleep cycles, alternating patterns of REM (Rapid Eye Movement) and NonREM sleep appear in all mammals, REM sleep, when humans report their most vivid dreams has been thought to be a "higher" brain function. With the platypus, (who sleep 18 hours a day) Dr. Siegel was trying to determine that REM sleep occurred in an earlier pre-mammalian life form a monotreme. Thereby possibly putting the origins of REM sleep, back much earlier in evolutionary time than previously thought, to reptiles and birds. (The New York Times article reporting on the experiment had a pithy quote: "Even a dinosaur may dream…") By determining when in evolutionary development REM sleep appears, Dr. Siegel hopes to find clues to its function; to date, no one really knows why we dream.

After several stages of Non-REM sleep where the brain seems at rest, there is this mysterious desynchronized state where the brain is wide awake, but the body is paralyzed – or more accurately subject to involuntary movements – it is the time of our deepest sleep, when human subjects report the most vivid dreams. In REM the neural substrates responsible for our critical self-reflection fail us. We feel intense emotions and are left with fragmentary images, while the rational, decision-making part of our brains, the pre-frontal cortex, is quiet. Why? The adaptive function of the "dream state" is unknown. Thus Dr. Siegel’s inquiry into animals with unique sleep patterns like the platypus, which he studies both through observation of behavior and by monitoring electrical readings of the brain.

While sleep forms a huge part of our daily existence, much about it remains a mystery and has only recently been studied. With our society’s increasing attention to sleep, and use of sleep aids, sleep research is going through a renaissance of sorts, and is increasingly into the news. When I spoke to Dr. Siegel he said there is clearly a connection between in his sleep research and effects of Prozac (SSRIs), which he is interested in exploring. Serotonin is one of the neurotransmitters in the "off" position during REM sleep, and there are categories of anti-depressants that significantly diminish REM sleep, (the effects of which are unknown). Sleep deprivation can temporarily alleviate depressive symptoms, but many more studies and investigations are needed to understand mechanisms that trigger REM sleep and how they might relate to what we call "depression."

See also: Jerome Seigel laboratory website: www.npi.ucla.edu

< back to top > |

| |

|

|

Song Lines

Imagine finding your way across the Australian Outback with a song as your only guide. As if the notes were tracks to follow left by an animal that created all the landforms you pass through. Long ago in Dreamtime, animal ancestors created the world: they left sink holes where they made love, caves where they slept, cliffs where they fought, each animal a song, telling their story in connection with the land. An aborigine learns his animal’s song and walks in their tracks, unraveling the story of his animal in the land as he witnesses the landforms the animal created. Singing and walking s/he keeps the animal alive under the earth still dreaming up the land, and the land healthy too. The Song Line is both song and track in the land, with it the aborigine is never lost.

Bruce Chatwin describes these practices in The Songlines, a book about his travels in the Australian Outback, and what it means to be nomadic. The more one reads, the aborigine cosmogony is so deep that it is ever slips out of one’s grasp. But something in the idea of Dreamtime, the practice of walking in the land to keep it alive is familiar. When I am out trekking in the mountains, I feel the land animate as a creative force; my task is to travel and observe, sing its praises. Watch the moon reflect in a tarn, and you cannot help but wonder at the Dreamer. Dreamtime the last song in the play is the closest I come to expressing these ideas, and bringing the arc of the play full circle.

A platypus is dreaming up the world, but doesn’t know he dreams. Captured by a scientist who is studying REM sleep, the platypus suddenly becomes aware of the notion of dreaming and wants desperately to see his dreams in order to escape from the tank. Platypus meets scientists daughter, Prozak, who is also in quest of her dreams about her dead mother; through her music, ritual, and descent into a coma, the platypus enters a dream to wake her up. My favorite moment is at the end of the play, when she sings "Dreamtime," dedicating it to her friend Frankie, the platypus, and he appears in the audience with his epiphany, nudging his fellow audience members: "Hey, I’m dreaming… I’m dreaming. This is my dream!"

< back to top > |

| |

|

|

Dreams

You wake in the morning, shake sleep out of your eyes over a cup of coffee. Any dreams? Most often you’ve forgotten to remember. You wake up thinking about deadlines, late to work, and there’s no one to remind you: “Any dreams?” We all have them. Every night...

It’s a mystery why we dream, like sleep, no ones really knows the full reason. We dream to consolidate memory, we dream to forget, it doesn’t matter why we dream, dreams are manifestations of our unconscious, dreams are fragments of the world consciousness, many theories... and yet our dreams are so intimate, haunting in their emotional accuracy.

I have a friend who listens to dreams. He quietly listens to my own voice telling the dream, until I can start hearing it too. Sometimes he asks a question, or asks me to describe something further. It’s so simple. But by the end of the cup of coffee, the dream is present, in the room in all its depth. Something I nearly tossed away like a pair of grungy socks becomes full of import and connection to my life. Can I live my life this way?

Perhaps, our dreams give us a taste of our origins: who we are free to fly, walk through walls, live outside our bodies and the confines of our self, inhabiting many places, times and people simultaneously. Perhaps, this is what excites the scientists in the play, Arvin and Susan, when they discover the platypus’ REM sleep resembles that of a human infant’s sleep. There is something very ancient in dreams, prehistoric, as necessary as the platypus or a dinosaur to our evolution, for us as individuals and as a species to become who we are. Any dreams?

See also: Little Course of Dreams by Robert Bosnak

< back to top > |

| |

|

|

Science and Myth

Science in its popular form posits ultimate human victory over human suffering and death, disease will vanish, and conditions will continue to improve. It is shiny and white like a lab coat. Myth and ritual are darker, muddy, emerging from the earth, making the eternal pain of living and dying bearable, meaningful in some way. Both are necessary and yet have become increasingly isolated in their relation to each other. We live in an increasingly fast paced, technologically society that does not have time for much ritual, but still has not done away with human suffering. We have access to images of human suffering in real time round the clock; but what do we do when pain touches our lives? Depression and drug treatment are one response, there are also virtual mythic worlds and games. But it still seems to be in the shared acts of story telling and ceremony that we still seem to find peace, and closure.

There is certainly a point at the outer edge of science, on the lip of what cannot be explained where science and myth meet. Scientific description blossoms into metaphor, myths give insight into how our unconscious mind may work. Susan, the other scientist in the play working at Arvin’s lab, reads about Australian aboriginal philosophy and finds in it a metaphor for her own experimental work on memory consolidation in REM sleep. Both are descriptions of consciousness, positing models yet to be fully proven. Both share in being the astounding creations of human brains reflecting upon themselves to perceive the "world."

See also: Flesh and Stone The Body and the City in Western Civilization by Richard Sennet

< back to top > |

| |

|

|

SSRIs

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) is a class of popular antidepressants of which Prozac is the most famous member. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter at the heart of our neural information system with receptors spread through out the body. Interestingly, there is a concentration in the heart – providing a link between cardiac disease and the depression that often accompanies it. People with "low" levels of Serotonin (there is as yet no direct way of measuring this in patients) take SSRIs to inhibit the reuptake of Serotonin at the receptor site increasing the levels of Serotonin the neural synapse and over time often having a powerful mood elevating effect. Culturally, the drug has become a seemingly animate force in our public dialogue about medication and mood disorders in books such as "Listening to Prozac" and "Prozac Nation."

Recently, in the UK a meta-study from the Public Library of Science was released and reported in the Guardian (February 26, 2008) causing quite a stir. The study examines many past studies not released to the public and compares them with the bulk of studies funded by drug companies that were, and comes to the surprising conclusion that Prozac is not proven to be much more effective than placebos. This comes at a time when the British National Health care service is putting much more funding into making cognitive based talk therapy available to their clients. The UK, despite widespread use of Prozac, has always had a slightly more critical view of the drug than in the United States; the first studies on Prozac’s possibly increasing the incidence of suicide in teenagers being first publicized there.

A follow up article in the Guardian (sited below) with contributions from writers with different perspectives and experiences with the drug is a good collection of opinions in response to this announcement. Core points of a debate about the widespread use of mood stabilizers are touched on in personal ways that are worth reading. There are clearly some people whom Prozac has “saved” their lives made it possible to function and participate in daily existence. There are others who through the loss of a teenager through a suicide while taking Prozac, feel this news as an even harsher indictment of a rush to legitimize a drug treatment, without full knowledge of effectiveness or disclosure of side effects. Therapists wonder over the placebo effect, and argue eloquently that a drug does little without talk therapy even as it is increasingly prescribed by GPs with no psychological backup. There is the ongoing critique that drugs are a much easier answer to these problems and more time efficient, (I might also add making someone a lot more money than talk therapy which is hard to commoditize). There is also a debate as to whether antidepressants while alleviating surface symptoms, actually help people tackle underlying causes of depression: death of a loved one, low self-esteem. And even how define the spectrum of "mental" illness or mood disorder, with the diagnosis of depression being a relatively recent phenomenon, perhaps shaped by the development of drugs to treat it. But over 40 million people are taking the drug, which while it has become a little like worn out Hollywood starlet of sorts, still deserves deeper thought.

See also: www.guardian.co.uk

< back to top > |

|

Suicide and Genetics

This is the darkest corner of the play. Prozak’s mother commits suicide and leaves her daughter depressed and wondering if the same will happen to her. What is a suicide in a family? Someone exits and leaves the door ajar for others to follow. A dark wind blows through the door. A possibility. A drafty secret. Talk to anyone who has one suicide in their family and there are often more; the shadow of a single suicide reaches across several generations.

I’ve always admired my maternal grandmother, an artist with a long neck, which she disguised with glass beads, and a bit of a stutter. She made me scrapbooks, and perfected her technique of deep color etching. I slept in her studio with wasps crawling from cracks in the ceiling and a large etching press. At a certain point in a life of battling depression, she thought it would be cleaner, less of a burden, to kill herself, and she did so very efficiently, boxes tied with string and labeled in her strong block print. There is something stoic in her action. She meant to help her daughter, but it was hurtful as any suicide is. And the door opened a crack, and yawned darkness, beyond my mother’s next drink.

My mother is a recovering alcoholic, chronically depressed, but determined to stay alive. I admire that in her. As in clouds there are big holes where sunshine and blue sky radiate. She is at times happy enough to make it all worthwhile. Recently has been making conscious efforts to "feed the good wolf." Whatever that it is: Feed the good wolf. Living with my mother, as she lived with her mother, one gets used to being in the proximity of depression. Understanding what a powerful leviathan it is, which needs many tools to shape it into something one can live with, or make go away.

With suicide genetics can create an undertow of inevitability, as strong as the environment; is it within the individual’s ability to swim against the familial tide? Prozak struggles to comprehend her mother’s suicide by going into her dreams, her music, imagination, and forms of self-expression. She tries swimming in whatever genetic pool she has been given, flailing around yet staying afloat. Arvin wishes to understand the source of this pain to be able to treat, it before his daughter dives too deep. His frustration is being so close to comprehending so much about how the brain functions and yet so far from a practical dialogue with his daughter. He cannot spare her the pool she has plunged into, nor help her swim.

< back to top > |

| |

|

|

Dreamtime

In Australian Aboriginal mythology, the time when the animal ancestors created the world, both a long time ago, but also occurring in the present moment. The animals still are asleep under the earth dreaming up the world. In walking the land and singing an animal’s song (see Song Lines), an aborigine is invoking Dreamtime, linking past and present creation, and keeping the land and the spirits alive.

< back to top >

|

|

|

the story : the music : get the goods : stage the play : dive deeper : become us

home : contact us

|

|